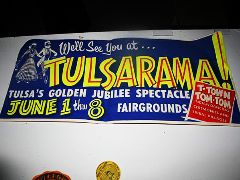

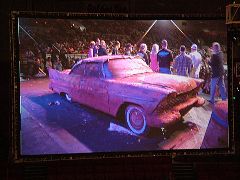

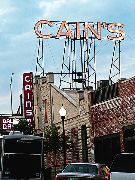

In 1957 the good citizens of the city of Tulsa, Oklahoma celebrated that state's 50th anniversary within the union with a town festival called — in classic atomic age style — "Tulsarama." A proud city built on oil fortunes, Tulsa had long possessed a streak of dynamic forward-thinking among its boosters and captains of industry; in its early architecture one can see the city's yearning to be considered a peer to more cosmopolitan Midwestern cities such as Chicago and St. Louis, and by mid-century Tulsa's importance as a music capital was well-established. How could such a city best celebrate a half-century of progress, and at the same time celebrate its vision of the half-century to come? Time capsules were nothing new in 1957, but they were very much in vogue. It was decided that Tulsa-centric materials would be gathered and placed into such a capsule, to be secreted away for 50 years in order to better help the shadowy, mysterious Tulsans of the future better understand those who lived in the era of Sputnik, Elvis Presley and President Eisenhower. Surely many Tulsans in 1957 could remember 50 years before, when Oklahoma officially stopped being Indian Territory and became the 46th state; times sure had changed since then, and who could possibly imagine how different the world of 2007 might be? And then somebody came up with an idea so crazy, it just had to be done: Why not put an entire, brand-new automobile into the time capsule? Phone calls were made, good ol' boys shook hands, and before long a factory-fresh 1957 Plymouth Belvedere had been donated to the cause. Why a Belvedere? According to one of the '57 Tulsarama organizers, it was because such a car represented "an advanced product of American industrial ingenuity with the kind of lasting appeal that will still be in style 50 years from now." A contest was initiated, too: Entrants filled out a small postcard on which they guessed what the population of Tulsa would be in 2007. The winner (or his or her nearest living relative) would receive the Belvedere and the contents of a bank account seeded with $100 in June, 1957. So many entries were received that it became necessary to record them on a reel of microfilm, which would be enclosed in the time capsule with the car. And so it came to pass that on Saturday, June 15, 1957, the good citizens of Tulsa lowered the car into a custom-built concrete vault under the county courthouse lawn. To protect it from five decades of stasis in the earth, the mammoth automobile was sprayed liberally with Cosmoline (a substance similar to petroleum jelly, used to rust-proof guns, machinery and other metal items) and vacuum-packed in a specially-made multilayered plastic bag. A number of items were placed in the car by the townsfolk, including a case of Schlitz beer (donated by late local jazzman Clarence Love), the "contents of a typical woman's purse" (tranquilizers, cigarettes, an unpaid parking ticket, etc.), photographs and other sundries. Gasoline and oil were included, too, in glass bottles placed in the trunk; in a contemporary news report, a man speculated that by 2007, cars might very well run on "solar power, or something like plutonium." Some kids signed their names in pen on the whitewall tires; others threw things like bottle caps and coins into the vault at the last moment. A more traditional time capsule — a metal cylinder filled with delicate and official bits and pieces, then welded shut — was placed next to the car, sitting upright in a special cradle like an egg in an egg cup. And then the lid went on, the sod was replaced, and Tulsa went about its business for 50 years. That second half-century, sadly, saw Tulsa suffer from growing pains. As in many Midwestern cities, masses of middle-class citizens fled traditional neighborhoods to the sprawling comfort of suburbs, taking with them the services of local merchants, who too often relocated to the hinterlands as well. Downtown Tulsa's astonishing Art Deco buildings began to fall by the wayside as businesses moved their offices to the handful of soulless skyscrapers constructed in the next 50 years. And now it's 2007, and this week marks the 50th anniversary of the original Tulsarama festivities. Being both a car nerd and an amateur historian, I was intrigued by the legend of the buried Belvedere, and decided that I should attend the unearthing if at all possible. Enter Bud Norman, an old friend of mine with a passion for what I'll call Route 66 Americana: Diner food, dive bars, wigwam-shaped motels, roadside attractions, etc. I told him a few weeks ago about the Belvedere and he immediately said, "Let's go." So yesterday — Friday, June 15, 2007 — Bud and I squeezed into his red Mazda Miata and headed to Tulsa. I drove on the way down, easily putting the miles behind us in the little roadster. We were hoping to get downtown to witness the actual raising of the car from its tomb, which was scheduled for 12:00 noon, but just outside Tulsa we ran into a major traffic snarl. All eastbound traffic was being diverted from three lanes into one, and that one lane was stopped because a grain truck had spilled probably a ton of grain from one of its underside hopper chutes onto the highway. As we waited in that interminable dead stop on the highway, I found a radio station playing an old cowboy song called "Riding into Tulsa," and Bud and I looked at each other and laughed. At the end of the song the DJ broke in excitedly and told us, "A 45 of that very song is in the time capsule with the Belvedere...and we've just heard that the car is out of the ground now, and they're putting it onto a flatbed truck to be taken to the civic center..." Well, goddammit. We decided to just head into downtown anyway, figuring we could park and walk around, maybe find some place to eat. After making it through the jam, we made good time into the center of Tulsa, where we ran into another dead stop. I looked around and realized that I had — by sheer coincidence — driven directly to the spot where the car had just been unearthed. And as we sat there hopelessly mired in traffic quicksand, I looked to the intersection ahead and saw, wrapped in filthy brown plastic, the shape of a 1957 Plymouth, atop a trailer pulled by a truck. "Look, Bud!" I pointed, and we both watched the curious sight go by. Eventually we found a random parking spot against a curb, fed the meter and started looking for a place to eat. By chance, we had parked just around the corner from the front office of the Tulsa World, the city's daily paper. My friend Jennifer works there, so we dropped in. The security guy hadn't seen her and couldn't reach her; we left a message and walked around the corner looking for the source of the delicious smell of beef cooking. We spied a place called Coney Island (which seems to be a popular moniker for fast food joints in Tulsa, as I counted three discrete businesses using versions of the name), and on our way toward it, we happened to notice this place: Orpha's Lounge. "You wanna get a beer?" Bud asked. Though I was actually pretty hungry, I couldn't resist the curiosity, and we went in. Orpha's is a little like Moe's Tavern, but (surprisingly) cleaner. As we walked through the door, which is situated at the top of a sudden and steep cement incline seemingly designed to throw drunks off-balance, a besotted, grey-haired man greeted us with, "Boy, I'm glad you fellas are here. Now they'll have somebody new to make fun of." The dozen or so others in the bar casually eyed us and went back to their drinking. Bud and I sat down for cold one-dollar draws of Miller High Life and soaked up the atmosphere. I also soaked up three beers, and I think Bud matched me. We got suggestions from the locals as to where to eat, I tried reaching Jennifer at the World again via the barmaid's cell phone, and after a bit we stumbled hungry and slightly drunken into the daylight. We ate at a place called Billy's, which specializes in char-broiled burgers, chicken sandwiches and the like, then headed back to the car so I could retrieve my camera (actually borrowed from Miss J. Pants), which I had left secured in the trunk. We set out walking, first back by Orpha's, so I could take the photo above, then continuing aimlessly around downtown Tulsa. Bud and I soon stumbled upon the first of many unique buildings we would see over the afternoon: The Adams Building, which is on the National Register of Historic Places: This ornately-carved structure, which first served as the Mincks-Adams Hotel, was built by a man named I.S. Mincks in preparation for the 1928 International Petroleum Exposition, which brought many investors and oilmen into the city. Today it serves as office space. An adjacent building, much taller but roughly the same age, appeared to be abandoned, with multiple broken windows boarded over with plywood. When we walked by it on street level, though, there appeared to be offices and/or storage inside, so perhaps it wasn't as bad as it looked. Still, its derelict appearance detracted from the Adams and other nicely-kept buildings in the area. As we walked on, Bud and I encountered church after church after church, most featuring gorgeous and expressive architecture. As we chased a tall, distant steeple some blocks away, we came across these churches one by one: And finally the tremendous, deliriously beautiful steeple which we had walked blindly toward revealed itself: Built in 1929, the Boston Avenue Methodist Church is, according to the Tulsa Preservation Commission, the world's "first church designed in a strictly American style of architecture." Its tower soars 258 feet into the Oklahoma sky and is capped with a sculptural topknot of what appears to be steel and glass. It is truly a spectacle to behold, and Bud and I both stood and stared at it for quite some time. We turned back toward downtown and walked up Boston Avenue, which is currently — like much of downtown Tulsa — undergoing road and sidewalk construction. At every corner, vast pools of muddy red water ringed with sticky red clay prevented us from making a simple street crossing without venturing into traffic. Half-finished brickwork lay abandoned everywhere; piles of black and red brick sat idle. Where were the workers? As we made our way back to the car, we came across a few more interesting buildings and bits of signage: That Atlas Life sign, by the way, is typical in style to a number of others in downtown Tulsa...and this particular one was made in Wichita by Claude Federal, which was once the mightiest neon sign company on earth. Bud and I were both a little hot and swampy from the long walk in the warm, humid afternoon. "Let's drive around," he suggested. He popped the top down on the Miata and the moment we hit the road, we started to cool off. Bud wondered aloud where one might find either Archer or Greenwood streets, and I recognized the reference to the Bob Wills song "Take Me Back to Tulsa." (In it, Tommy Duncan sings, "Would I like to go to Tulsa? Boy I sure would! Let me off on Archer and I'll walk down to Greenwood.") Literally seconds later, we came to Greenwood; we turned left onto it and drove on. And doubly weird, only a couple blocks down the road, we came across Archer Street. I suggested we pull over so I could take a picture of Bud. That third sign on top of the post reads: Black Wall Street. As soon as I saw that, something clicked inside me. I jerked upright with a gasp and looked around at the block of neat brick buildings in the sudden realization that I was standing at ground zero of the Tulsa Race War of 1921. The only sign of the horror was a small plaque set into the sidewalk; on this day, everything was totally quiet and still. The only thing moving in the neighborhood was this rotating sign atop a building a block away: We got back in the car and drove some more, following neither rhyme nor reason. I told Bud I needed to pee, and we pulled up to a gas station. I put the camera in the trunk and walked toward the building. The parking lot was swarming with mostly brown faces and the air was filled with bone-rattling bass from car stereos and the obscenity-riddled shit talk of the wrong side of the tracks. My urinary plans were foiled when I came face to face with a sign that read: DUE TO THIS BEING A HIGH CRIME AREA WE HAVE NO PUBLIC TOILET SORRY. I returned to the car to find Bud leaning on the trunk enjoying a smoke and relayed the sign's message to him. His response: "Well, let's find a rich part of town to piss in." And soon thereafter we did, again purely by accident. We found ourselves cruising along the wide Arkansas River on Riverside Drive, and out of curiosity, Bud pulled into the neighborhood to our right, a tony, hilly enclave stacked deep with beautiful old-money homes and luxury cars. I reminded him of my need to take a leak, and he pulled back onto Riverside; almost immediately he noticed what appeared to be a public park with a toilet building, but which to our delight turned out to be a restaurant and bar located right on the bank of the river. I did my business and we both ordered beers, which we drank sitting in the shade of an umbrella as ducks begged us for food. Across the way from this little oasis stood a very tall, lime-green-and-black apartment building that seemed to be inspired by The Jetsons. Sadly, I didn't have the camera handy, but Bud was fixated on it, and I have to admit that I, too, wondered what it would be like to live 200 feet in the air in a building that looks like a stack of frisbees. Eventually we had wasted enough time and set off for the civic center for the main event: the unveiling of the Belvedere. We parked several blocks away in a parking garage and walked down Boulder once again, past the Tulsa World offices and then to our right a couple more blocks until the city complex appeared before us, directly in our path. To our left was the courthouse, where we could see a team of men with heavy equipment filling in the empty concrete vault in the earth. To our right was the library, and straight ahead was the civic center. The vast plaza between the street and the hall was almost completely empty, save for Bud and me and a handful of what we guessed to be homeless folks. It was a little like The Omega Man. Where is everybody? Just as I opened the door, I overheard a woman on her cell phone: "...no, I didn't see it. I heard they unwrapped it and it was so bad they just wrapped it back up..." "Uh-oh," I thought. Several hundreds of people were inside the civic center, already staking out places in line, though 45 minutes remained until the doors were to open. I picked up our will-call tickets and headed into the "B" hall to get in line for a soda. That hall is hosting an invitational car show this weekend, and the selections were, to a number, immaculate: Sadly I ended up standing in line almost the entire time, and got precious few photographs. This is pretty much how I saw the whole show — from the concession line: At long last we were able to enter the arena and take our seats: Though we were at the far end of the room from the stage, the giant video screens helped us see what was going on onstage. (Please note that many of the following photos are shots of these screens, so the quality varies vastly. Sorry.) The show was hosted by the tag team of Tulsarama chairwoman Sharon King Davis and a guy who I think might have been the DJ who played "Riding into Tulsa" earlier in the day. They introduced another local radio personality, who was dressed in Marilynesque fashion: "Keep drawing this thing out," Bud sighed, and I had to agree. We didn't come to hear about the "fifties makeovers" being made available all day Saturday at some local spa. We came to see the car. Make with the car! And then, with the introduction of legendary hot rod builder (and American Hot Rod star) Boyd Coddington, who had been retained in hopes of being able to start the car's engine, they made with the car: Sure enough, instead of a gleaming, well-preserved piece of 1950s rolling sculpture, there was the same ghostly and grimy shape we'd seen being trucked by flatbed earlier in the day, still wrapped in its filthy plastic shroud. A confused mishmash of sounds erupted from the audience — applause, moans, laughs, cries of, "No!" Coddington explained to the crowd that as feared, the car had indeed apparently spent years at least partially submerged in its underground vault, essentially forever destroying its potential as a motor vehicle. A team of tech nerds from, I believe, Oklahoma State was introduced, and as a lonesome disco ball spun to the mournful tune of a wailing saxophone, they proceeded to peel back Miss Belvedere's "protective" plastic veil: It was almost too much to bear. Every millimeter of the car was covered with a layer of rust, and much of that was topped with an additional layer of greenish algae. I had the unsettling sensation that I was vouyeristically participating in a sort of public autopsy. Then they opened the hood: The engine fared no better than the rest of the car. One of the OSU tech kids pulled out the dipstick to "check the oil," only to discover that the crankcase was, not surprisingly, filled with brackish water. Next came the trunk, which had housed the bottles of gasoline and oil and the case of Schlitz: Totally ruined, every bit of it. And to top off the tragedy, in the back seat was discovered what was believed to be the destroyed remains of the precious microfilm containing the entries of thousands of participants in the contest to win the car: Then things got a little brighter. The separate time capsule, apparently intact after 50 years, was opened and — to everyone's delight and relief — the interior and its contents were perfectly preserved: The very first thing they found inside, on top of everything else, was a 48-star American flag, reputed to have been flown over the Oklahoma State Capitol: More stuff was retrieved from the capsule, including the aforementioned 45-rpm record "Riding into Tulsa," a bumper sticker reading MADE IN OKLAHOMA BY INDIANS and the official 1957 Tulsarama proclamation. And, fortunately for a very few entrants in the contest to win the car, a number of the actual entry postcards were included in the time capsule; since the microfilm appears to have been ruined, these paper entries are now the only ones in play. I'd had enough, and so had Bud. We left the civic center and walked back out into the eerie silence of downtown Tulsa. I wanted to go over to the spot where the car had been buried all those years, hoping to find the plaque in the sidewalk that had marked its tomb for 50 years, but it appears to be missing. This is all that remains: I picked up a pinch of red clay from the site as a souvenir, and we walked back to the Miata. Bud called his cousin to see about crashing at her place, but she, like Jennifer, was incommunicado. We drove around a while longer, eventually stumbling across Cain's Ballroom in our roundabout sojourn. As we walked the block, a band inside pumped out a convincing rendition of Neil Young's "Rockin' in the Free World": Finally we decided just to split town after grabbing a bite. We found a nigh-abandoned diner called Kelly's and ordered food with lots of coffee. As we waited for our grub, the waitress loudly asked if anybody in the room had their car windows down, because — unbeknownst to us — a downpour of rain had started. Bud moved faster than I've ever seen, realizing that his top was down. We rode back to Wichita sitting on seat liners made of Spanish-language newspapers. I learned a lot about Tulsa yesterday, and today in the writing of this. It has a lot in common with Wichita, including the visible layers of boom and bust left like rock strata in any given city's downtown. It's got beauty and squalor, clear signs of progress (including diesel-electric hybrid city buses) and plenty of ugly scabs. As it stands today it may not exactly have lived up to the most optimistic visions of the 1950s, but it continues to adapt and survive. Unlike a certain Plymouth. |